A Better Approach to Updating, Restructuring, and Simplifying the Sentencing Guidelines Manual

The last in a series of essays on the 2024-25 U.S. Sentencing Commission guideline amendment year

The U.S. Sentencing Commission titled the signature amendment of the 2024-25 guideline amendment year, “Simplification of the Three-Step Process.” It runs almost 600 pages and is the first restructuring of the Guidelines Manual in almost 40 years. The amendment removes one of the steps in the current three-step federal sentencing process.

For those not fully familiar with the federal sentencing system, here is the Sentencing Commission’s explanation of the three-step process.

In the wake of Booker and subsequent cases, the Guidelines Manual provided a three-step process for determining the sentence to be imposed, which is reflected in the three main subdivisions of §1B1.1 (Application Instructions) (subsections (a) through (c)). The three-step process can be summarized as follows: (1) the court calculates the applicable guideline range and determines the sentencing requirements and options related to probation, imprisonment, supervision conditions, fines, and restitution; (2) the court considers policy statements and guideline commentary relating to departures and specific personal characteristics that might warrant consideration in imposing the sentence; and (3) the court considers the applicable factors in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a) in deciding what sentence to impose (whether within the applicable guideline range, or whether as a departure or as a variance (or as both)).

With this amendment, the Commission eliminates “departures” from the Guidelines, what was Step Two of the sentencing process. As amended, the process will now be only two steps rather than three. The first involves calculating the recommended guideline sentencing range. It is the easier part. It’s not easy, just easier. Anyone can do it. It involves formulas and math and lots of instructions. It doesn’t require wisdom; just a few facts and lots of technical training in how the Guidelines work.

But then, after the calculations are done, it’s time for the judging, the new Step Two. The Commission’s technical explanation of this step is, “the court considers the applicable factors in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a) in deciding what sentence to impose.” A more helpful explanation is that this is the part of the process where a human being reflects on everything that ought to be considered in coming up with a just sentence – the numbers but much more. The history and characteristics of the offense and offender. The impact of the offense – and the sentence that might be imposed – on the offender and the community. All of the conflicting purposes of sentencing. Those who were scarred by the crime and who might be haunted by it. The imperative to treat everyone fairly and avoid unwarranted disparities: Equal Justice Under Law. And that we’re all more than the worst thing we ever did. It’s the part of the process full of values and principles that point in different directions; the part that flummoxes most people, including most judges; the part we hope will lead to something for justice and for the hope of it all.

With the elimination of departures from the Guidelines Manual, the Commission also eliminates nearly all guidance on the second step, everything outside the numerical formulas. Judges are now on their own. The Commission has nothing to contribute. Under the new guideline architecture, courts will continue to calculate the guideline sentencing range under Step One. They will continue to use what almost all agree are many flawed formulas found in the Guidelines, especially the drug and fraud guidelines. But now, when the courts move to the judging part of the sentencing process, they will be left without guidance from the Commission. As I said in the immediate aftermath of the vote on this restructuring, I’m not sure why the Commission thinks this will better achieve the statutory purposes of sentencing reform. I’m not sure why it thinks it has nothing — no wisdom at all — to help the judges here. I’m not sure why this won’t result simply in greater unwarranted sentencing disparity. It strikes me that eliminating the guidance has made the sentencing process less structured, less consistent, and worse.

Take the drug guideline. The fundamental structure of the guideline and of Step One of the sentencing process is unchanged. The critique of the guideline that it relies too heavily on drug type and quantity and only minimally accounts for culpability — something I discuss in our essays on A Better Federal Drug Guideline and The Failure of Drug Sentencing Policy Reform — remains. This critique is part of what the Commission heard at the Drug Sentencing Roundtable it held last year and left largely unaddressed.

But worse, under the amended system, after calculating the guideline range, the sentencing court is left with no guidance to determine the appropriate sentence that is sufficient but not greater than necessary to achieve the purposes of sentencing; no guidance to go beyond the rote numbers. The Commission chose to eliminate lots of guidance from the drug guideline and from other guidelines that are relevant in drug cases, which all indications suggest was helpful to courts in this part of the process. For example, the following guidance for cases involving reverse sting operations was eliminated.

Downward Departure Based on Drug Quantity in Certain Reverse Sting Operations.—If, in a reverse sting (an operation in which a government agent sells or negotiates to sell a controlled substance to a defendant), the court finds that the government agent set a price for the controlled substance that was substantially below the market value of the controlled substance, thereby leading to the defendant’s purchase of a significantly greater quantity of the controlled substance than his available resources would have allowed him to purchase except for the artificially low price set by the government agent, a downward departure may be warranted.

And this guidance on efforts to avoid detection –

An upward departure nonetheless may be warranted when the mixture or substance counted in the Drug Quantity Table is combined with other, non-countable material in an unusually sophisticated manner in order to avoid detection.

And this on unusually high purity cases –

Upward Departure Based on Unusually High Purity.—Trafficking in controlled substances, compounds, or mixtures of unusually high purity may warrant an upward departure, except in the case of PCP, amphetamine, methamphetamine, hydrocodone, or oxycodone for which the guideline itself provides for the consideration of purity (see the footnote to the Drug Quantity Table). The purity of the controlled substance, particularly in the case of heroin, may be relevant in the sentencing process because it is probative of the defendant’s role or position in the chain of distribution. Since controlled substances are often diluted and combined with other substances as they pass down the chain of distribution, the fact that a defendant is in possession of unusually pure narcotics may indicate a prominent role in the criminal enterprise and proximity to the source of the drugs. As large quantities are normally associated with high purities, this factor is particularly relevant where smaller quantities are involved.

And this on duress or coercion, applicable not infrequently when a family member is drawn into a drug conspiracy —

If the defendant committed the offense because of serious coercion, blackmail or duress, under circumstances not amounting to a complete defense, the court may depart downward.

Why was all of this guidance — and so much more — eliminated? Will sentencing courts make better decisions without it? Will they make better decisions without any guidance from the Commission on Step Two? Did anyone suggest all the current guidance was wrong?

There was a better way to restructure the Guidelines Manual to finally address the Supreme Court’s decision in Booker and simplify the Guidelines too, or at least I think there was. Professor Steve Chanenson and I spelled out what we believe would have been a far better approach to restructuring the Guidelines in a letter to the Sentencing Commission after it published its proposed amendment for public comment. The full letter is below. Our approach certainly would have been more difficult for the Commission than just cutting pages and pages of guidance from the Guidelines Manual. But it might have also led to better sentencing outcomes and a system to be proud of and to last for decades to come.

- - -

January 29, 2025

The Honorable Carlton W. Reeves, Chair

United States Sentencing Commission

One Columbus Circle, NE

Suite 2-500, South Lobby

Washington, DC 20002-8002

Dear Judge Reeves:

We hope this finds you and all at the Commission well.

This is in response to the Commission’s Proposed Amendment to the Sentencing Guidelines, Simplification of the Three-Step Process, published in the Federal Register on January 2, 2025.[1] We appreciate the opportunity to share a few thoughts with you on this significant proposal.

We were gratified to read last summer that in this 40th anniversary year of the Sentencing Reform Act (SRA), and now the 20th anniversary year of the Supreme Court’s decision in Booker v. United States,[2] the Commission would be reflecting on the core goals of the Sentencing Reform Act, the progress that has been made towards meeting them, and what actions might be taken now, and in the future, to further them. We were also pleased to see the Commission unanimously publish the Simplification of the Three-Step Process proposed amendment and issues for comment to further those core goals and better reflect the Booker jurisprudence in the Sentencing Guidelines.

Better reflecting Booker in the Guidelines is well past due. So is simplification of the Guidelines. Before Booker, the federal sentencing Guidelines were criticized for being overly complex, overly harsh, overly reliant on such quantifiable offense factors as drug quantity and loss, and contributing to a system of ever-growing plea bargaining and the “vanishing” jury trial.[3] Twenty years after Booker, the system is even more complex. It is still overly reliant on quantifiable factors. There are fewer jury trials today, not more, even though the Booker merits majority opinion was expressly predicated on vindicating the Sixth Amendment jury trial right. The average federal sentence has increased since Booker. There is more unwarranted disparity in sentencing between and within the circuits and districts, with some courts still sentencing within the Guidelines regularly and others doing so rarely.

Not all these problems, of course, can be laid solely on the doorstep of the Guidelines and the Sentencing Commission. But we strongly believe that the Commission is well situated to reform federal sentencing policy and advance solutions to these problems. As we’ve stated before in prior comments to this Commission, we think changes to the Guidelines’ fundamental architecture are essential for reforms to be effective. And we think the Commission is the best-positioned institution to help structurally reshape federal criminal and sentencing law and practice for the better.

We applaud the Commission for the issues for comment and an ambitious proposed amendment, which we see as an important opening step in a multi-year process to adjust, at long last, the Guidelines to both recognize the landmark changes brought by Booker to federal sentencing and incorporate in the Guidelines the legal mandates and realities of the post-Booker advisory guideline system. If the Commission makes the needed structural changes, it will necessarily address some of the longstanding systemic problems with the Guidelines.

Our views on the proposed amendment and issue for comment are simple: the current three-step process unnecessarily complicates the federal sentencing process, causes much confusion for practitioners and defendants alike, and likely leads to greater unwarranted disparities in sentencing outcomes. At the same time, we do not think simply eliminating departure guidance from the Guidelines Manual is the right approach to better achieving the Sentencing Reform Act’s goals, which we believe are still very important and worth pursuing. Nor do we think eliminating departure guidance is entirely consistent with the SRA and other enactments by Congress.

There are deep flaws in how all three steps of the process currently operate, some of which are the result of Commission decisions, and others are the product of longstanding flaws in the federal criminal code. Together, they undermine effective sentencing policy and important constitutional values. Booker has a long lineage and incorporating it into the Guidelines credibly means grappling with that lineage and laying out a vision for a better criminal law and sentencing system.

We think the Commission should address all these challenging and critical structural issues by developing a path to a federal criminal law and sentencing architecture consistent with best practice and constitutional values. The Commission has the capacity to develop this better architecture, and we offer some ideas for that here. Our suggestions are derived mostly from best practices from the states and foreign countries that have adopted sentencing guidelines and from the foundational Supreme Court criminal law decisions that animated much of Booker.

We hope the Commission will continue this collaborative policy development process to craft a revised proposal. We think great work on sentencing requires the broader perspective we suggest here, and the Commission is uniquely positioned to accomplish it in a bipartisan and legislatively realistic way.

Each Step of the Sentencing Process Is in Need of Reform

The Sentencing Guidelines issued by the 1987 Commission – and sentencing guidelines issued by many states and nations that have adopted them – are based on a two-step architecture. That architecture requires users to first – in Step One – determine a recommended sentencing range based on a formula developed by the sentencing commission, and second – in Step Two – determine whether to sentence the individual defendant outside that recommended range or at a particular point within the range.

This is the process Congress had in mind when it enacted the Sentencing Reform Act in 1984. It is the process the Commission had in mind when it promulgated the Guidelines in 1987. It is the process Congress had in mind when it promulgated the PROTECT Act in 2003. And it is the process that is used by many states and nations that have adopted sentencing guidelines.

The current three-step process was not designed by anyone. It is not part of any cohesive strategy. It is an accidental artifact of a sharply divided Supreme Court in 2005 that expected Congress to quickly reconsider the design of federal sentencing policy after Booker and adjust it. Justice Stephen Breyer famously said in the Booker remedial majority opinion, “Ours, of course, is not the last word: The ball now lies in Congress’ court. The National Legislature is equipped to devise and install, long-term, the sentencing system, compatible with the Constitution, that Congress judges best for the federal system of justice.”[4] Congress never picked up that ball – and neither has the Commission, until now – and we’ve lived with an unnecessarily complex and confusing three-step guideline system for over 20 years.

We applaud the Commission for picking up the ball today. But calling the right play is essential now that you have the ball in your hands. Simply eliminating departure guidance isn’t a sound strategy. We think all three steps of the current process are flawed. Fixing them will require a multi-year plan at the Commission as well as congressional action. We think the Commission’s first task is to devise that plan, which will include refinements to the Guidelines – and eventually the federal criminal code, too – to more fully embrace the constitutional values underlying Booker, Blakely, and foundational criminal law decisions that are Booker’s pedigree.

We start, below, with thoughts on Steps Two and Three, as this is the focus of the Commission’s proposed amendment. Ultimately, though, changing Steps Two and Three will be insufficient without also addressing Step One. The Guidelines’ architecture must fit together with the architecture of federal criminal law to create a system that meets the goals of sentencing reform and the constitutional values at the heart of Booker.

The Complexity and Confusion Inherent in the Current Steps Two and Three

The complexity and confusion around Steps Two and Three of the sentencing process and arising from Booker stem in significant part from what the Commission itself long ago recognized as the “tension” between the requirements of 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a) and those in 28 U.S.C. §§ 991 et seq. As then-Commission Chair Patti Saris testified before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security in 2011, 28 U.S.C. § 994(e) directs the Commission to “assure” that the guidelines and policy statements reflect the “general inappropriateness of considering the education, vocational skills, employment record, family ties and responsibilities, and community ties of the defendant” in determining the length of imprisonment.[5] And the Commission, on its own, adopted policy statements to limit the use of other offender factors. All this while § 3553(a) and post-Booker jurisprudence puts no limits on the consideration of offender factors but instead mandates that sentencing judges consider “the history and characteristics of the defendant” in all cases.[6]

Judge Saris told the Subcommittee that “[o]ver the course of its history, the Commission has ensured that the departure provisions set forth in the Guidelines Manual are consistent with this directive. Yet under the current advisory regime, judges consider those very factors under § 3553(a) and often arrive at sentences below the guidelines range as a result of such consideration . . .”[7] Judge Saris, on behalf of the full Commission, asked Congress to resolve the disconnect between the directives to the Commission and the directives to the courts. It never did. And because the Guidelines Manual generally limits the use of offender factors, the complexity and confusion have persisted, with two separate paths (steps) – with different application standards in the district court and review standards in the appellate court – to considering offense factors not articulated in the Guidelines and offender factors generally.

Resolving that complexity and confusion would be a good thing for many reasons. But to do it, as Judge Saris recognized, requires amendments to the SRA to create a consistent body of law (statutory and case law) and policy. If the “tensions” identified by Judge Saris are resolved, the Guidelines could then follow best practice in the states and around the world of a two-step sentencing guidelines process. But under current law, we believe simply eliminating all departures from the Guidelines Manual and leaving sentencing judges with no guidance on Step Two of the sentencing process would be both inconsistent with current statutory law and a grave policy mistake.

Eliminating departure guidance from the Guidelines Manual would be inconsistent with much of the Commission’s statutory role as laid out in the SRA – to guide the exercise of judicial sentencing discretion – and would lead to even more inconsistent outcomes and even greater unwarranted sentencing disparities. It would also encourage adding more factors to Step One – greater “factor creep” beyond what’s already occurred – and would be inconsistent with the SRA and various congressional directives to the Commission, including 28 U.S.C. § 994(e).

Judge Saris also recognized in her testimony – which was based on the Commission’s lengthy departure report in 2003 – that underlying the PROTECT Act was a clear recognition and endorsement of the role departures play in the federal sentencing process. While the PROTECT Act came before Booker and was certainly mostly about curtailing departures, its provisions can’t simply be ignored. With the Act, Congress directly amended the Guidelines Manual to regulate the use of departures. It did not eliminate departures. It recognized and authorized their use, including upward departures, in specifically delineated circumstances. The Commission has not made public any legal analysis nor suggested any legal basis or authority simply to overrule those laws and strike all departure provisions from the Guidelines (including provisions added by law). Especially in light of the recent Supreme Court decisions on the role of administrative agencies, we think the Commission ought to be extremely cautious before moving so directly against acts of Congress. At the very least, the Commission should publish for comment any legal analysis that it might have done around its authority in this area.

The better approach for the Commission to take, we believe, both from a legal and policy perspective, is for the Commission to draft an amended Guidelines Manual that creates a two-step process that includes departure-like guidance from the Commission to sentencing courts on Step Two. This guidance would identify in the Guidelines Manual those “secondary” offense factors – factors not included as Specific Offense Characteristics (SOCs) or other offense level adjustments in Step One – courts ought to consider in determining whether to sentence outside that recommended range or at a particular point within the range. This guidance would be based on the Commission’s genuine expertise in crafting the Guidelines and identifying grounds, particularly offense-based grounds, for sentencing outside the otherwise-applicable range or at a particular point within the range.

As to offender factors, the Commission will need to revisit the existing policy statements, mostly in Chapter Five of the Guidelines Manual, in light of the post-Booker relevance of them in all cases. The Commission should review judicial experience and practice surrounding these factors and also social science studies and findings around them. This could lead to the type of guidance on these factors in the Manual as the Commission provided this past amendment year in relation to youthful offenders.

All of this policy development should include working collaboratively with Commission stakeholders – as the Commission often does – to try to develop a consensus proposal. But it should be done in the context of a genuine understanding of and vision for the overall architecture of federal sentencing and federal criminal law. We outline, below, why we think so, what a better two-step process might look like, and why it all leads us to the policy conclusion not to eliminate all departures from the Manual.

We think this more holistic perspective and process, which would simplify the Guidelines, address mandatory minimum sentencing statutes, and reform federal criminal law – could lead to a far better, politically viable, and sustainable sentencing system – and criminal justice system – for the coming decades. Yes, the Commission would have to work with Congress to enact amendments to the Sentencing Reform Act – and perhaps later, the federal criminal code itself – to ultimately implement this better system. We view the Commission as an essential leader in creating this better system and progress on this proposal as an essential step in the path towards it.

Why Departure Factors Are Critical to an Effective Two-Step Architecture, and Why the Overarching Federal Criminal Law Architecture Must Be Considered and Should Be Reformed

As the Commission recognized in the introduction to the original Guidelines Manual, the intent of Congress in enacting the Sentencing Reform Act was to create a system of guidelines that achieve the goals of proportionality – “a system that imposes appropriately different sentences for criminal conduct of differing severity” – and reasonable uniformity – “narrowing the wide disparity in sentences imposed for similar criminal offenses committed by similar offenders.”[8] To that set of congressional goals, the Commission added a third goal of its own, avoiding complexity in the guidelines system in order to better achieve the two congressional goals. The Commission concluded that “[t]he greater the number of decisions required and the greater their complexity, the greater the risk that different courts would apply the guidelines differently to situations that, in fact, are similar, thereby reintroducing the very disparity that the guidelines were designed to reduce.”[9]

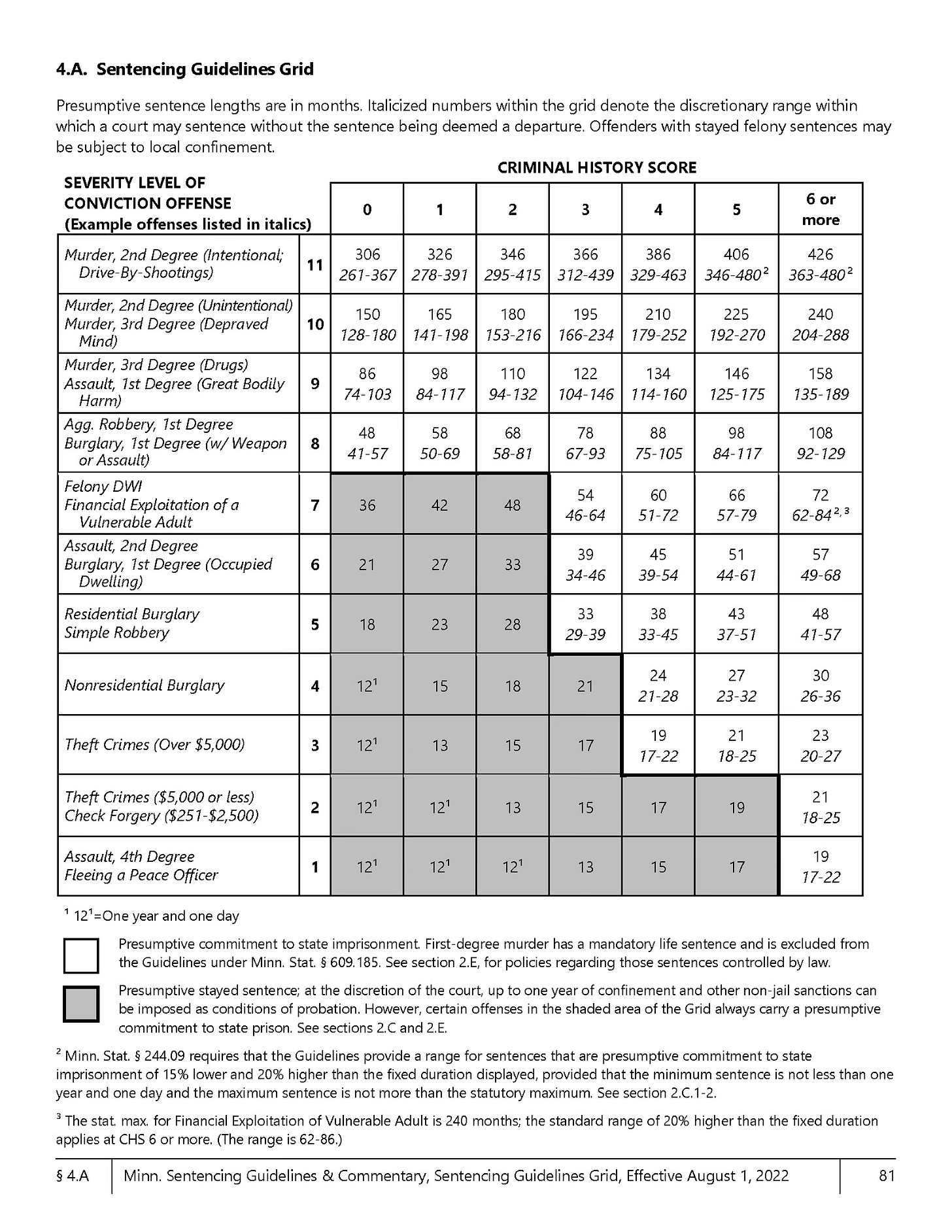

For many state sentencing commissions, meeting these three goals – proportionality, reasonable uniformity, and avoiding excessive complexity – in Step One of the sentencing process is not all that difficult. This is because many state criminal codes that were adopted after the American Law Institute issued the Model Penal Code in the 1960s adequately differentiate crime severity in their criminal laws through a statutorily defined severity grading system. Factors that distinguish grades of theft or assault, for example, are built into these state codes, so that assault causing great bodily injury may be graded as Assault in the First Degree, with lesser degrees of assault (Second Degree, Third Degree, etc.) defined not just by the absence of great bodily injury but based on other defined offense factors, like weapon use.

These codes embraced the principles the Supreme Court partially adopted in a series of cases in the 1970s, In re Winship,[10]Mullaney v. Wilbur,[11] and Patterson v. New York,[12] that if a factor makes a substantial difference in “punishment and stigma” it ought to be codified and proven by the government beyond a reasonable doubt.[13] When a criminal code is well constructed in this way, the sentencing commission need not generally build in non-statutory aggravating and mitigating factors into a sentencing Step One algorithm. It can avoid most of the controversy around “relevant conduct,” for the code achieves adequate proportionality. The result is a relatively simple process for Step One of sentencing for the commission, the litigants, and the judge. The Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Grid, attached as Appendix A, is an example of a simple sentencing grid based on the proportionality embodied in a reformed criminal code.

In nearly all states, the counts of conviction along with criminal history are the primary, if not sole, determining factors used to set the sentencing range. This was hoped for in the federal system too, when code reform was proposed and when it passed the Senate. The Sentencing Reform Act was part of that legislation, and the sentencing guidelines were intended to work hand-in-hand with the reformed code.

However, code reform was not enacted in the federal system. The Sentencing Reform Act was severed from the legislation and enacted separately. And as a result, the 1987 Commission was pushed to embrace a modified real-offense approach. That approach necessitated fact-finding by judges about key offense facts that might have otherwise been offense elements and that raised the constitutional problems leading to the Booker ruling. We think the Commission must consider this history in its deliberations about Guideline architecture. The Commission should design a reformed Guideline architecture that is part of a larger vision of a reformed criminal law and sentencing system. Such a system would ultimately include a charge-driven sentencing system where judicial fact-finding would play a significantly reduced role in Step 1, setting the guideline range, but where judicial sentencing judgment would still be central to Step 2, deciding on the ultimate sentence.

The failure of federal code reform means that the current federal criminal code does not generally do a good job of differentiating crimes of differing severity. There are, to be sure, some crimes for which the federal code adequately differentiates severity, such as homicide, and for those crimes, the Guidelines can and are generally simpler. But for most federal crimes, including the “big four” – fraud/theft, drugs, immigration, and firearms – the code does not well-differentiate offense severity, requiring the Commission to fill the void to achieve proportionality. A $100 wire fraud and a $1 billion wire fraud are embodied in a single statutory crime.

The 1987 Commission recognized that to achieve proportionality given the nature of the federal criminal code, the federal guidelines had to identify those factors that made “a substantial difference in punishment and stigma” and build them into Step One. The Commission also recognized that there is a “tension” among the mandates of uniformity, proportionality, and simplicity. It set out its thinking on this tension in the introduction to the Guidelines Manual:

Simple uniformity – sentencing every offender to five years – destroys proportionality. Having only a few simple categories of crimes would make the guidelines uniform and easy to administer, but might lump together offenses that are different in important respects. For example, a single category for robbery that included armed and unarmed robberies, robberies with and without injuries, robberies of a few dollars and robberies of millions, would be far too broad.

A sentencing system tailored to fit every conceivable wrinkle of each case would quickly become unworkable and seriously compromise the certainty of punishment and its deterrent effect. For example: a bank robber with (or without) a gun, which the robber kept hidden (or brandished), might have frightened (or merely warned), injured seriously (or less seriously), tied up (or simply pushed) a guard, teller, or customer, at night (or at noon), in an effort to obtain money for other crimes (or for other purposes), in the company of a few (or many) other robbers, for the first (or fourth) time.

The list of potentially relevant features of criminal behavior is long; the fact that they can occur in multiple combinations means that the list of possible permutations of factors is virtually endless.[14]

The first Commission readily conceded that the appropriate relationship among different factors is difficult to establish, “for they are often context specific.” It also appreciated that “[t]he larger the number of subcategories of offense and offender characteristics included in the guidelines, the greater the complexity and the less workable the system. Moreover, complex combinations of offense and offender characteristics would apply and interact in unforeseen ways to unforeseen situations, thus failing to cure the unfairness of a simple, broad category system.”

In the end, the Commission tried to identify and build into Step One the distinctions that made a significant difference in sentencing decisions – a “heartland” of factors and how they apply in typical cases – and to leave to departures less frequently occurring factors and where the identified factors, in context, “significantly differ from the norm.” Departures would have a significant role in such a system. The Commission decided that to achieve the balance of uniformity, proportionality, and simplicity, it needed to identify those non-heartland factors and situations in the Guidelines Manual to guide judges in Step Two. This guidance was based on the Commission’s expertise in developing the Guidelines and the empirical analysis it used to develop the Guidelines.

Of course, over the last 38 years, there has been much “factor creep” and with it, growing complexity and the addition into Step One of factors of lesser importance. The Guidelines Manual has grown significantly since 1987 as the Step One algorithms have added new factors. We think part of the Commission’s simplification project must consider and ultimately address factor creep, consider the larger goals of code reform, and create a system that at Step One is largely driven by primary offense factors proven beyond a reasonable doubt. As to Step Two, we believe the guidance contained in the current commentary – guidance for non-SOC factors or the unusual context for SOCs or other adjustments – is critically important in encouraging judges to consistently reach an appropriate sentence. As a matter of sound sentencing policy, we do not believe that vital guidance should be lost.

For example, in the guideline for second-degree murder, the commentary includes this: “[i]f the defendant’s conduct was exceptionally heinous, cruel, brutal, or degrading to the victim, an upward departure may be warranted.” In the drug guideline, the commentary includes this: “If, in a reverse sting (an operation in which a government agent sells or negotiates to sell a controlled substance to a defendant), the court finds that the government agent set a price for the controlled substance that was substantially below the market value of the controlled substance, thereby leading to the defendant’s purchase of a significantly greater quantity of the controlled substance than his available resources would have allowed him to purchase except for the artificially low price set by the government agent, a downward departure may be warranted.” This type of guidance is valuable for encouraging a more consistent approach to the sentencing process. Of course, the guidance on reverse stings begs the question of whether quantity should be a driving (primary) sentencing factor in drug cases and makes clear why the Commission’s simplification project must take on more.

The alternative – striking all commentary – will leave litigants, judges, and probation officers with no guidance on Step Two. We think that would be a big mistake. It is inconsistent with the Commission’s mandate under the Sentencing Reform Act to leave the various courtroom actors bereft of this centralized advice. Even if the Commission simply lists in each Chapter Two and Three guideline aggravating and mitigating factors not contained in the guideline that may be relevant (or in Chapter Four for criminal history that over- or understates a criminal record), sentencing participants will have a common foundation and starting point as they engage with the Step Two process. And with that foundation, they are more likely to follow a consistent and transparent path to reach a sentence that fits the crime. Moreover, that list of aggravating and mitigating factors, which should be heavily influenced by judicial and case experience as filtered through the Commission’s normative judgment, will facilitate important data collection at the Commission for the listed factors and analysis of the efficacy of the applicable guideline. This virtuous circle of advice and feedback only works if the Commission continues to provide comprehensive guidance and collect relevant data.

As described above, we think the Commission should capitalize on its unique position and composition to improve the federal sentencing system. While it cannot accomplish this alone, it can be the catalyst for a better criminal justice future. A modest start could be to convert existing departure language into a list of aggravating and mitigating factors for courts to consider in Step Two. There are, of course, other ways to move things forward. However, abandoning all the current departure-style recommendations for sentencing judges would be an abdication of the Commission’s responsibilities and a body blow to the goal of consistent, proportionate sentencing in the federal courts.

The Commission should, over the next year or so, commit to the difficult task of laying out a vision for a reformed criminal law and sentencing system that would reduce the number of primary factors already in the Guidelines that may be used infrequently or that are not making a substantial difference in “punishment and stigma” and provide guidance for judges to consider recurring aggravating and mitigating considerations in Step Two. This could ultimately lead to a bipartisan adoption of a reformed criminal and sentencing law that is simpler, more consistent with the Booker jurisprudence and its constitutional lineage, and more effective at meeting the goals of the Sentencing Reform Act.

- - -

We know this is a lot to chew on. We hope some of these comments and suggestions are helpful to you. We know that we are asking the Commission to do great work. We do so, because we think the Commission is an institution capable of it.

Please let us know if there’s anything more we might do to assist you in your work. We are grateful for this opportunity to weigh in. And please know we are pulling for your success and for the best possible federal criminal law and sentencing system.

Sincerely,

/s/ Jonathan J. Wroblewski

Director, Semester in Washington Program

and Lecturer on Law

Harvard Law School[15]

/s/ Steven Chanenson

Professor of Law

Faculty Director, David F. and Constance B. Girard DiCarlo

Center for Ethics, Integrity and Compliance

Charles Widger School of Law

Villanova University

APPENDIX A

[1] U.S. Sent’g Comm’n, Sentencing Guidelines for the United States, 90 Fed. Reg. 128 (January 2, 2025), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2025-01-02/pdf/2024-31279.pdf.

[2] 543 U.S. 220 (2005).

[3] See, e.g., Frank O. Bowman, The Failure of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines: A Structural Analysis, 105 Colum. L. Rev. 1315 (2005); National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, The Trial Penalty: The Sixth Amendment Right to Trial on the Verge of Extinction and How to Save It (July 2018).

[4] Booker, 543 U.S. at 265.

[5] Testimony of Judge Patti B. Saris, Chair, United States Sentencing Commission, Before the Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security Committee on the Judiciary, United States House of Representatives, October 12, 2011.

[6] See also, 18 U.S.C. § 3661.

[7] Id.

[8] U.S. Sent’g Comm’n, Guidelines Manual, Chapter 1, Part A (2024).

[9] Id.

[10] 397 U.S. 358 (1970).

[11] 421 U.S. 684 (1975).

[12] 432 U.S. 197 (1977).

[13] Patterson v. New York, 432 U.S. at 226 (1977) (Justices Powell, Brennan, and Marshall dissenting).

[14] U.S. Sent’g Comm’n, Guidelines Manual, Chapter 1, Part A (2024).

[15] Both of our affiliations are included here for identification purposes only.