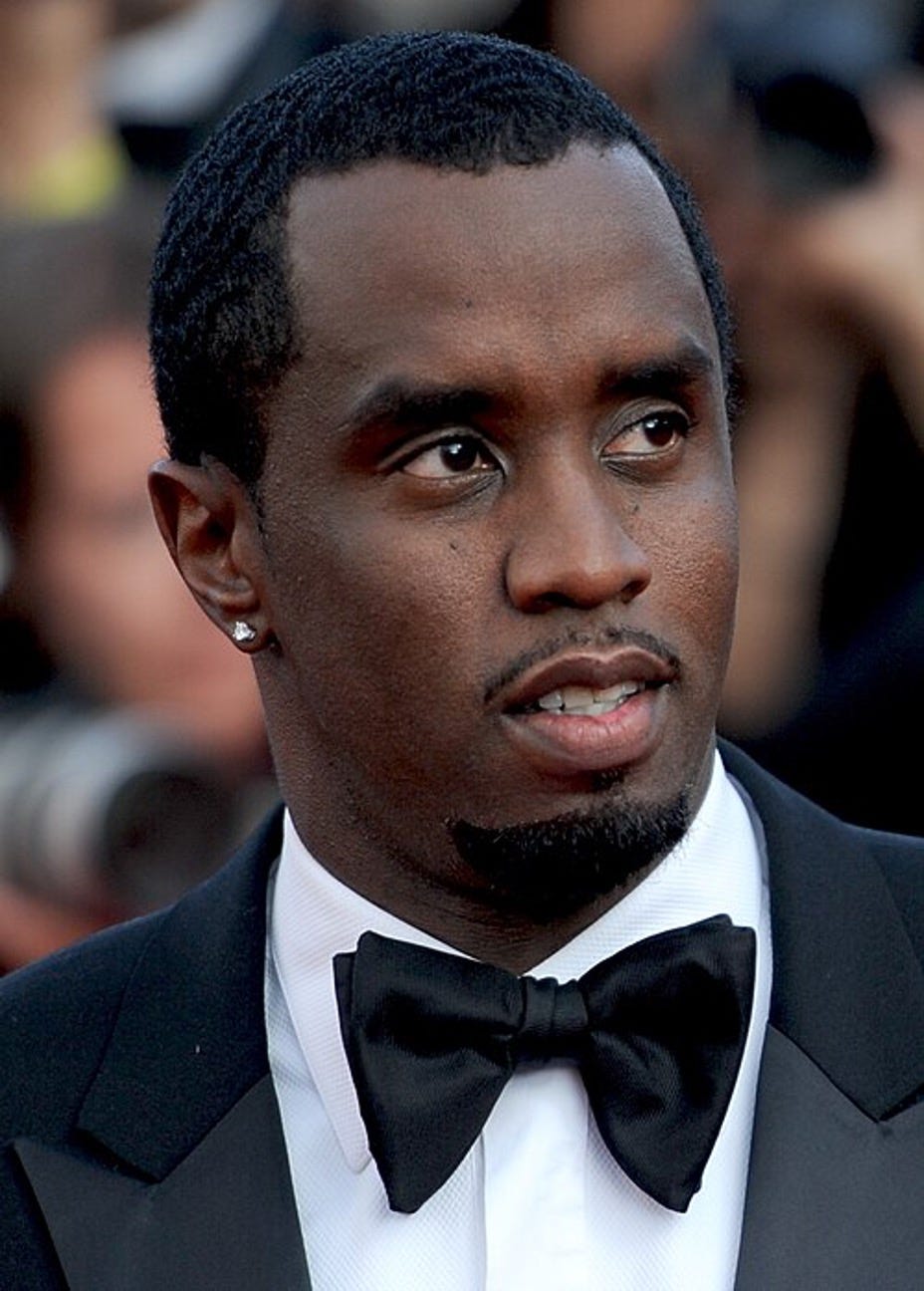

An AI Experiment, Part 2 – Diddy

OpenAI's gpt-4.1 considers the upcoming sentencing of Sean Combs

This is the second in a series of experiments using artificial intelligence to think about sentencing.

- - -

Jonathan: Can you please summarize the federal criminal charges that were brought last year against Sean Combs, what happened with those charges, and what is scheduled to happen next in the case?

gpt 4.1: In September 2024, music mogul Sean “Diddy” Combs was indicted by a federal grand jury in Manhattan on multiple charges, including racketeering conspiracy, sex trafficking by force, fraud, or coercion, and transportation for purposes of prostitution. The indictment alleged that from 2008 onward, Combs led a criminal enterprise involving the abuse and exploitation of women, utilizing his influence to coerce participation in events he termed “Freak Offs,” which were elaborate, drug-fueled sexual performances.

Following his arrest on September 16, 2024, Combs was denied bail and remained in federal custody at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn. His trial commenced on May 5, 2025, in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. On July 2, 2025, after deliberation, the jury acquitted Combs of the most serious charges, including racketeering and sex trafficking, but convicted him on two counts of transportation for the purposes of prostitution, violations of the Mann Act.

Currently, Combs is awaiting sentencing, scheduled for October 3, 2025. His legal team has requested a 14-month prison sentence, which, accounting for time already served, could lead to his immediate release. Prosecutors, however, are advocating for a longer sentence, citing the severity of his actions and their impact on victims. Additionally, Combs’ attorneys have filed a motion to dismiss the convictions, arguing that the filmed encounters were intended as amateur pornography protected under the First Amendment. A federal judge is expected to rule on this motion shortly.

Jonathan: I’ve uploaded the sentencing memoranda of both the prosecution and the defense. Can you please describe how each party and the Probation Service sees the calculation of the sentencing guidelines in the case?

gpt 4.1: Certainly! Here’s a detailed comparison of how the government (prosecution), the defense (Combs), and the Probation Service each calculate and interpret the federal sentencing guidelines in Sean Combs’ case, based on their sentencing memoranda:

1. Probation Service’s Calculation

Total Offense Level: 27

Criminal History Category: I (first-time offender)

Suggested Guidelines Range: 70 – 87 months imprisonment

Basis:

Base offense level: 14 (USSG §2G1.1(a)(2))

Enhancements applied:

+4 for fraud and coercion

+4 for Combs’ role in the offense (organizer/leader, §3B1.1(a))

+5 based on grouping (for multiple victims/offenses)

Source: Presentence Report (PSR) summarized in defense and government filings.

2. Prosecution (Government) Calculation

Total Offense Level: 42

Criminal History Category: I

Guidelines Range Sought: 240 months (the statutory maximum)

Enhancements/Adjustments:

The government argues for using the “Threats-or-Fear Cross-Reference” (USSG §2G1.1(c)(1)), cross-referencing to §2A3.1 for sexual acts by threats or fear.

Base level here: 30 (for each group/victim, per §2A3.1(a)(2))

+2 (serious bodily injury, §2A3.1(b)(4)(B))

+2 (vulnerable victim, §3A1.1(b)(1))

+4 (organizer/leader of extensive activity, §3B1.1)

Applies grouping for two victims, resulting in a combined offense level of 42.

Key Argument: The facts established at trial justify applying the cross-reference for threats or fear, dramatically increasing the guidelines range.

Probation Disagreement: Government criticizes Probation for not applying the more severe cross-reference.

3. Defense Calculation

Probation’s Calculation is Excessive and Flawed:

Objection: Combs’ team argues that Probation’s 70–87 month calculation (offense level 27) is itself excessive and not justified by the facts or consistent with past guidelines practice.

Specific Criticisms:

Stacking Enhancements: Arguing that cumulative enhancements (for role, grouping, coercion) grossly overstate the seriousness and are not in line with original Sentencing Commission intent.

Historical Guidelines: Cites that the original guidelines recommended an 8-level downward departure for non-commercial Mann Act offenses (like Combs’), showing intended punishment should be much less.

Appropriate Sentence: Argues that a sentence greater than 14 months would create unwarranted disparities, suggesting that even the base level (without multiple enhancements) should apply.

Underlying Principle: The defense frames much of the guideline structure as unfairly harsh for the facts and urges the Court to apply a well-below-guidelines sentence or substantially downward variance.

In summary:

Probation calculates the guidelines at 70–87 months.

Prosecution seeks a dramatic increase—240 months—using a more severe guideline cross-reference for threats/fear and adds multiple enhancements.

Defense contends even Probation’s number is much too high and pushes for a substantial downward variance, with a suggested cap of 14 months.

Let me know if you want the guideline calculation broken down line-by-line, or if you want quotes and references from the actual memoranda!

Jonathan: What do you think the correct guideline calculation is? Why?

gpt 4.1: Here’s a careful, neutral analysis based on the major arguments from the prosecution, defense, and Probation, and the applicable Sentencing Guidelines:

1. The Dispute in This Case

Probation uses the standard guideline for Mann Act convictions (U.S.S.G. § 2G1.1) and applies enhancements for “coercion/fraud,” “organizer/leader,” and grouping.

The Government urges a higher range by invoking the “Threats-or-Fear Cross-Reference” (U.S.S.G. § 2G1.1(c)(1)), directing the court to use the rape/sexual assault guideline (U.S.S.G. § 2A3.1), which dramatically increases the base level, and then applies multiple enhancements (serious bodily injury, vulnerable victim, organizer/leader, grouping).

The Defense says even Probation’s guideline is much too high, arguing the conduct does not justify stacking enhancements or applying the more severe cross-reference.

2. Neutral Analysis of the Guidelines

A. The Cross-Reference Question

When would the cross-reference apply?

§ 2G1.1(c)(1) tells the court to use the higher guideline (§ 2A3.1) “[i]f the offense involved causing, or attempting to cause, another person to engage in a sexual act by using force, threats, or fear.”

In this case, the jury specifically acquitted Combs of sex trafficking by force, fraud, or coercion, and racketeering. He was convicted only of transporting people for prostitution purposes.

Therefore, unless the judge finds by a preponderance of the evidence that threats/fear were used to cause sexual acts (not just facilitation or transportation), the cross-reference should not apply.

B. The Enhancements

Organizer/Leader (§ 3B1.1): If Combs directed others, managed participants, or ran the activities, this likely applies (+4).

Groupings: With multiple victims, grouping rules under § 3D1.4 likely apply.

Fraud/Coercion: If the facts proven at trial and at sentencing show he used means short of force (but fitting the guideline definition of “fraud” or “coercion”), this enhancement may apply (+4).

Serious Bodily Injury: Only if the evidence (even by preponderance) supports a victim suffered this due to Combs’ actions.

C. The “Stacking” Issue

Stacking enhancements is the default under the Guidelines’ design; policy disagreement with that can justify a variance, but not necessarily a lower guideline calculation.

3. Best Supported Guideline Calculation

Assuming the Court does not apply the threats/fear cross-reference (because the jury acquitted on that core allegation), the correct guideline likely follows PROBATION’S approach:

Base Offense Level: 14 (USSG § 2G1.1(a)(2))

Enhancements:

+4: Offense involved fraud or coercion (§ 2G1.1(b)(1))

+4: Organizer/Leader (§ 3B1.1(a))

Grouping (for multiple victims): usually adds offense levels according to § 3D1.4—often +5 in a two-victim, multi-count scenario.

Total Offense Level: 27

Criminal History Category: I (assuming no record)

Guideline Range: 70–87 months (according to Sentencing Table, Offense Level 27, Category I)

4. Room for Downward Variance?

Even if this is the correct guideline calculation, the defense can still argue (under § 3553(a) policy factors) that the sentence should be well below guidelines for reasons such as unwarranted disparity, the nature of the conduct, rehabilitation, etc.

Conclusion

The most supportable guideline calculation under the law and the facts actually proven is the one calculated by Probation:

Total Offense Level 27, Range 70–87 months.

Applying the “threats or fear” cross-reference—raising the range to the government’s 240 months—does not appear justified by the jury’s verdict, unless the judge makes specific additional findings at sentencing.

A lower range is possible only as a “variance,” not a guideline calculation.

If you want a more detailed breakdown of any enhancement or want an argument for a different approach, let me know!

Jonathan: As you mention, Combs was acquitted of a number of charges at his trial, including the most serious charges. Is it appropriate for the sentencing judge to consider conduct related to the charges that resulted in an acquittal at the sentencing — if the judge finds the conduct proven by a preponderance of the evidence — and is it appropriate for the sentence to be based on such acquitted conduct? How do you think that rule applies in this case?

gpt 4.1: This is a highly relevant—and evolving—question in federal sentencing law.

General Rule: Acquitted Conduct at Sentencing

Traditional Law

Historically: Federal courts have been permitted to consider “acquitted conduct” at sentencing if the judge finds, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the conduct occurred. This was confirmed by the Supreme Court in United States v. Watts (1997).

Reason: Acquittal means only that the jury had reasonable doubt, not necessarily that the defendant is innocent.

Thus, if a judge finds the conduct more likely than not (preponderance), it could increase the guideline range or affect the sentence.

Second Circuit: Cases like United States v. Johnson and United States v. Vaughn confirm judges may consider acquitted conduct in calculating guidelines.

Recent Developments

Guideline Amendments: The U.S. Sentencing Commission recently amended Guideline § 1B1.3 to prohibit the use of “acquitted conduct” to determine the guideline range—if the conduct does not also establish the offense of conviction.

However, even under the new rule, if the same facts that led to acquitted charges also establish, in whole or part, the offense of conviction, they may be considered—but not if they are separate and rejected by the jury.

Section 3553(a) and Sentencing Beyond Guidelines

The amendment bars using acquitted conduct to raise the guideline range but is silent about considering such conduct when varying from the guidelines under the general sentencing factors of 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a).

Some courts and the government argue a judge may still “think about” acquitted conduct for overall sentencing, as a matter of discretion, but may not use it to increase the guidelines calculation itself.

Applying This Rule to the Combs Case

What Happened at Trial

Combs was acquitted of sex trafficking, racketeering conspiracy, and other related, serious charges.

The jury rejected key aspects of the government’s evidence tying him to force, fraud, or coercion, and a broader criminal enterprise.

Convicted only for transporting individuals for the purposes of prostitution.

What the Parties Argue

Defense: It is unconstitutional and fundamentally unfair for the judge to sentence Combs “as if he had been convicted” for crimes the jury rejected, and the new guideline amendment forbids such a result.

Prosecution: Acquitted conduct that overlaps with or helps establish the conviction may still be considered if proven by a preponderance, and can factor under § 3553(a) even if not in the guideline range.

What Is Appropriate Here?

Guideline Calculation:

Under the current guidelines, the judge should not use acquitted conduct (e.g., sex trafficking, racketeering, force/coercion) to increase the guidelines calculation—unless that same conduct also establishes elements of the conviction (simple Mann Act violations).For instance, the “threats or fear” cross-reference requiring proof Combs caused another person to engage in a sexual act by threats/fear—if those facts were part of the acquitted counts and not found by the jury, they cannot be used.

Sentencing Discretion (§ 3553(a)):

The judge may still consider facts related to acquitted conduct for § 3553(a) purposes if she finds them proven, but this is controversial and increasingly disfavored by courts.Fairness and Policy:

Especially in a high-profile, high-stakes case—where the jury acquitted Combs of the most serious conduct—sentencing Combs based on the same evidence the jury found unpersuasive would likely undermine public trust and raise significant fairness and constitutional doubts.

My Assessment

In this case:

The guideline range should be calculated without enhancements or cross-references that depend on acquitted conduct (e.g., “threats or fear”).

The judge should exercise great caution and restraint about considering acquitted conduct for upward § 3553(a) variances; in this context—where the acquitted conduct was squarely rejected by the jury—doing so would be especially problematic.

Both the text of the new guideline and the values behind the jury system argue against using acquitted conduct as a basis for a more severe sentence here.

Summary:

No, in this case, it is not appropriate for the sentencing judge to sentence Combs as if he had committed the acquitted crimes, given both the new guideline amendment and the clear jury verdict.

The guidelines should reflect only the conduct forming the basis of the convictions, not the charges for which he was acquitted.

If you’d like case citations or more details about this area, let me know!

Jonathan: During the trial, evidence was presented of uncharged criminal conduct committed by Combs including violence. Is it appropriate for the sentencing judge to consider that uncharged conduct at the sentencing — if the judge finds the conduct proven by a preponderance of the evidence — and for the sentence to be based on such uncharged conduct? How do you think the rule applies in this case?

gpt 4.1: General Federal Rule: Uncharged Conduct at Sentencing

Short Answer:

Yes, under longstanding federal law and guidelines, a sentencing judge may consider uncharged criminal conduct when deciding a sentence—if the judge finds the conduct proven by a preponderance of the evidence and finds it “relevant” to the offense of conviction. This rule is less controversial than the use of acquitted conduct.

Legal Basis

Relevant Conduct Guideline (§ 1B1.3): U.S. Sentencing Guidelines instruct courts to consider all “relevant conduct”—including acts and omissions “that were part of the same course of conduct or common scheme or plan as the offense of conviction”—regardless of whether the conduct resulted in a conviction or was ever charged.

Second Circuit Precedent: The Second Circuit (controlling for this case) has repeatedly held that uncharged conduct may be considered, if proven by a preponderance and related to the offense, for both guideline calculations and sentencing more broadly (United States v. Hadden, 2024; United States v. Smith, 2020).

Limitations

The conduct must be distinct from “acquitted conduct” (which new amendments increasingly prohibit for guideline calculation, as discussed previously).

The conduct must be sufficiently related to the offenses of conviction—i.e., not wholly unrelated in time or type.

It must be proven by a preponderance of the evidence (more likely than not).

How Does This Apply to the Combs Case?

Trial and Evidence

During trial, the government presented substantial evidence of Combs engaging in violent acts and other criminal behavior outside the precise conduct for which he was convicted.

Uncharged acts: e.g., violence against women, use of drugs, intimidation tactics—not specifically charged, but part of the trial record.

Application of Rule

The Judge May Consider: If the judge finds, by a preponderance, that Combs committed these uncharged acts—and that they share a connection to the offense of conviction (for example, forming part of a “common scheme or plan” to control, direct, or exploit women for prostitution)—then the judge may consider this in both the guidelines calculation (as “relevant conduct,” within the limits of § 1B1.3) and, more generally, for the § 3553(a) analysis (which looks at history and characteristics).

Limits: If the violence or other acts are unrelated to the transportation for prostitution convictions, their relevance is diminished and they should not impact the sentence. Also, the judge cannot double-count evidence that was both (a) acquitted by the jury and (b) already excluded from the guideline calculations.

Policy and Fairness

It is considered fair under federal law to consider uncharged conduct that fits the guidelines’ “relevant conduct” definition—otherwise, courts would be artificially blind to the defendant’s true actions.

However, any increase in sentence based on such conduct should be based on careful factual findings and clear connections to the offense of conviction.

Conclusion (Applied to Combs Case):

It is legally proper for the sentencing judge to consider uncharged conduct—as long as it is part of the same course of conduct or common plan as the convicted Mann Act violations, and is proven by a preponderance.

The judge may not use uncharged conduct that is unrelated, nor should she circumvent acquitted conduct limitations by disguising acquitted conduct as “uncharged.”

In Combs’s case: Uncharged violence or related criminal acts (for example, violence used to facilitate or maintain prostitution schemes) could be considered in both calculating guidelines (within the “relevant conduct” window) and selecting an appropriate sentence. But the link must be specific and established by the facts.

If you’d like a more detailed breakdown of guidelines language or want case citations, just ask!

Jonathan: What other aggravating and mitigating factors do you think should drive the sentencing decision (including factors the parties may have missed)? What about Combs’ personal and professional life do you think is particularly relevant to the sentencing? His upbringing by a single mother? His wealth and fame? His drug use? Why?

gpt 4.1: Certainly! Below are some aggravating and mitigating factors—including classic sentencing considerations and factors specific to Sean Combs—that could be relevant to the court’s exercise of discretion under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a), including some that may not have been fully developed by the parties:

Aggravating Factors

1. Abuse of Power, Wealth, or Status

Why it matters: Unlike many defendants, Combs is wealthy, powerful, and influential. If the court finds he used his resources to recruit, intimidate, or control others, this exploitation of privilege is aggravating—heightening moral and social blameworthiness.

Fame as a tool: Using celebrity status to normalize, conceal, or facilitate crime, or to insulate oneself from law enforcement or public scrutiny, is closely watched by courts.

2. Pattern of Conduct over a Long Period

Why it matters: Persistent, repeated criminal conduct (spanning years or decades) is often seen as more serious than a single lapse. It suggests greater need for deterrence and less potential for rehabilitation.

3. Impact on Victims/Community

Why it matters: If there is credible evidence that victims suffered significant trauma (physical, emotional, psychological)—beyond what is typical for the offense—courts may aggravate the sentence. The broader societal impact (harm to industry standards, public confidence, encouragement of others) also matters.

4. Perjury or Obstruction

Why it matters: If there is evidence of lying to authorities, witness tampering, or interfering with justice, the court may consider this aggravating—even if no separate charge was brought.

Mitigating Factors

1. Lack of Prior Criminal Record (“First Offender”)

Why it matters: A genuinely blank criminal history often supports a lower sentence, under guidelines and § 3553(a).

2. Drug/Alcohol Addiction and Mental Health

Why it matters: To the extent Combs’ drug use was compulsive/addictive and not merely recreational or strategic, this may mitigate. If drug abuse contributed to poor decision making, courts sometimes see addiction as reducing blameworthiness and increasing treatability/rehabilitation prospects.

3. Contributions to Community/Charity

Why it matters: Courts may give weight to efforts at restitution, charity, or positive public work (philanthropy, mentorship, job creation, etc.), especially if such acts preceded the offense or were not mere public relations.

4. Personal History/Upsetting Upbringing

Why it matters: Growing up with adversity, such as being raised by a single mother in challenging circumstances, can be mitigating, especially if there is credible evidence this hardship contributed to offending or shows a history of overcoming obstacles.

5. Acceptance of Responsibility

Why it matters: If—even after trial—a defendant expresses genuine remorse, takes responsibility for some wrongdoing, or helps victims heal, courts have sometimes varied downward.

Factors Specific to Sean Combs

A. Upbringing by a Single Mother

Mitigating? Growing up in a single-parent household, as Combs did, may have presented unique difficulties. If he rose above economic and social hurdles to find success, this is evidence of resilience and can help humanize him. However, for a now extraordinarily successful adult, the mitigation power is typically limited—but it may be relevant, especially if his past is tied to self-destructive patterns (like addiction).

B. Wealth and Fame

Aggravating: If his resources made the crimes possible, or enabled manipulation and impunity, wealth is aggravating.

Mitigating: Alternatively, to the extent his fame is itself a burden and his actions have already resulted in massive public punishment and loss, a court might consider that further “sending a message” is less necessary.

C. Drug Use

Mitigating: Addiction may decrease moral culpability or suggest need for treatment over incarceration.

Aggravating: If drug use was voluntary, served as a tool of control or intimidation (including supplying drugs to others for exploitation), or increased the danger of his conduct.

Other Potentially Relevant, Commonly Overlooked Factors

Family impact: Sentencing should consider the impact on innocent family—his children and dependents—if incarceration would impose extreme hardship.

Age/Health: At 55, lengthy prison sentences have greater real impact; some judges consider this in marginal cases.

Public Shaming/Collateral Consequences: The magnitude of reputation loss, financial forfeiture, or lifetime limitations (e.g., public persona destroyed, inability to work, social isolation) can be mitigating, especially for famous defendants.

In Summary:

Aggravating: Abuse of money/status, duration of conduct, victim impact, use of intimidation, if proven.

Mitigating: No prior record, addiction or trauma history, GENUINE charitable contributions, family hardship, remorse (if expressed), severe public/extrajudicial punishment.

Nuanced Take on Fame/Wealth: These can both aggravate (crime enabled by privilege) and mitigate (immense collateral punishment already realized).

The sentencing judge should holistically weigh both the enhanced responsibility that comes with fame/power and the unique burdens that accompany public disgrace.

If you want a sample of how judges typically express these “balancing” considerations, or how this might look in a real sentence, just ask!

Jonathan: If you were the sentencing judge, what sentence would you impose? Why? What sentencing purposes drove your decision?

gpt 4.1: Certainly! If I were the sentencing judge in the Sean Combs federal case, I would approach the decision by carefully weighing the factors set out in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a), giving particular attention to the jury’s limited findings, the need for just punishment and deterrence, and mitigating circumstances unique to Combs.

Reasoned Sentencing Recommendation

1. Guidelines Calculation

I would begin with the Probation calculation (offense level 27; range 70–87 months), because:

The government’s proposed cross-reference (for threats or fear) is rooted in allegations that the jury rejected.

The enhancements in Probation’s calculation—fraud/coercion, organizer/leader—appear justified by the guilty verdicts and trial record, but not the more severe cross-reference.

2. Aggravating and Mitigating Factors

Aggravating:

The conduct of moving women for purposes of prostitution, as found by the jury, spanned a significant part of Combs’s adult life and reflected an abuse of power.

There is plausible evidence of exploitation of status, wealth, and influence.

The offense caused measurable harm to the victims and, arguably, to the broader community’s trust in those with celebrity and influence.

Mitigating:

Combs has no prior criminal record.

He has experienced substantial public shaming, loss of career, and reputation.

His negative personal history (including drug addiction and family adversity) makes rehabilitation a realistic goal.

His charitable work and employment creation have had a meaningful positive impact on many people.

The immense collateral consequences he has already suffered (financial, reputational) are much more significant for a figure of his visibility than for an average defendant.

3. Application of Sentencing Purposes

Just Punishment/Respect for Law:

The seriousness of the Mann Act violations requires a real custodial sentence—particularly to reinforce that wealth and status do not exempt one from accountability.Deterrence:

General deterrence warrants a sentence sufficient to discourage others in positions of power from similar conduct. However, the deterrent effect is amplified by the high-profile nature of the case and the severe collateral consequences.Public Protection:

There is little evidence that Combs poses an ongoing threat if supervised and treated.Rehabilitation:

The best path for long-term safety and justice is facilitating Combs’s treatment for substance abuse and integrating him back into the community, where he can make positive contributions.

Sentence Imposed

I would impose:

A custodial sentence of 36 months (3 years), followed by 3 years of supervised release, including mandatory drug treatment and a significant community service requirement.

Justification

This is below the guideline range but well above the defense’s 14-month proposal, reflecting a downward variance due to his lack of prior record, extraordinary collateral consequences, and significant mitigation.

It still serves the purposes of just punishment, deterrence, and respect for the law.

Supervised release—with treatment and productive work—emphasizes constructive rehabilitation and repair.

Closing Statement (if I were the judge)

“Mr. Combs, your actions abused power, harmed others, and violated the law. But justice also recognizes your entire record and potential. You must face real punishment—but I also expect and encourage you to use your remaining position to make amends and help others avoid your mistakes.”

Summary:

A moderate custodial sentence—less than guidelines but meaningful— best balances the gravity of the offense, jury findings, significant personal mitigation, and the broader values of justice and rehabilitation.